In Conversation

Image shown: Ciara McMahon (foreground). Time donation

In the second of our In Conversation series celebrating Arts and Health Month this November, artsandhealth.ie talks to Ciara McMahon, a visual artist and GP based in Dublin, about the ways in which her medical and art practices inform each other and the impetus behind the deAppendix cultural space co-located with her general practice.

Ciara McMahon is a visual artist and a GP. She runs deAppendix, a cultural space which is co-located with Amaranta Family Practice in Blackrock, Co. Dublin. Her art practice is frequently collaborative and performative, realised through photography, film and site-specific installation. Ciara holds a degree and masters in Fine Art Practice and Contemporary Art Theory from NCAD. Ciara studied medicine in Trinity College Dublin and undertook specialist training in general practice as part of the Royal College of Surgeons GP training scheme.

artsandhealth.ie caught up with Ciara in the Amaranta Family Practice. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Can you tell me about your medical background and what drew you to study medicine in the first place?

I went straight into medicine after Leaving Cert. I was then and still am interested in the human body, how it works, it’s really fascinating. And then I really enjoy people, trying to figure out what makes them tick. So arising from the two of those interests medicine fitted.

To be a GP you have to do post-graduate training. So I did that, I went into practice full time and then I trained as a psychotherapist as well – another two or three years part-time training while I was working as a GP. I really enjoyed it because it’s another way of looking at people; it’s another paradigm of understanding us – including myself – our interactions and our way of being. But to work as a therapist while also working as a GP, I found it was too much, too draining. A lot of general practice is psychologically influenced so I felt that the semi-psychotherapeutic contact I had and have within my day-to-day GP practice was and is satisfying enough.

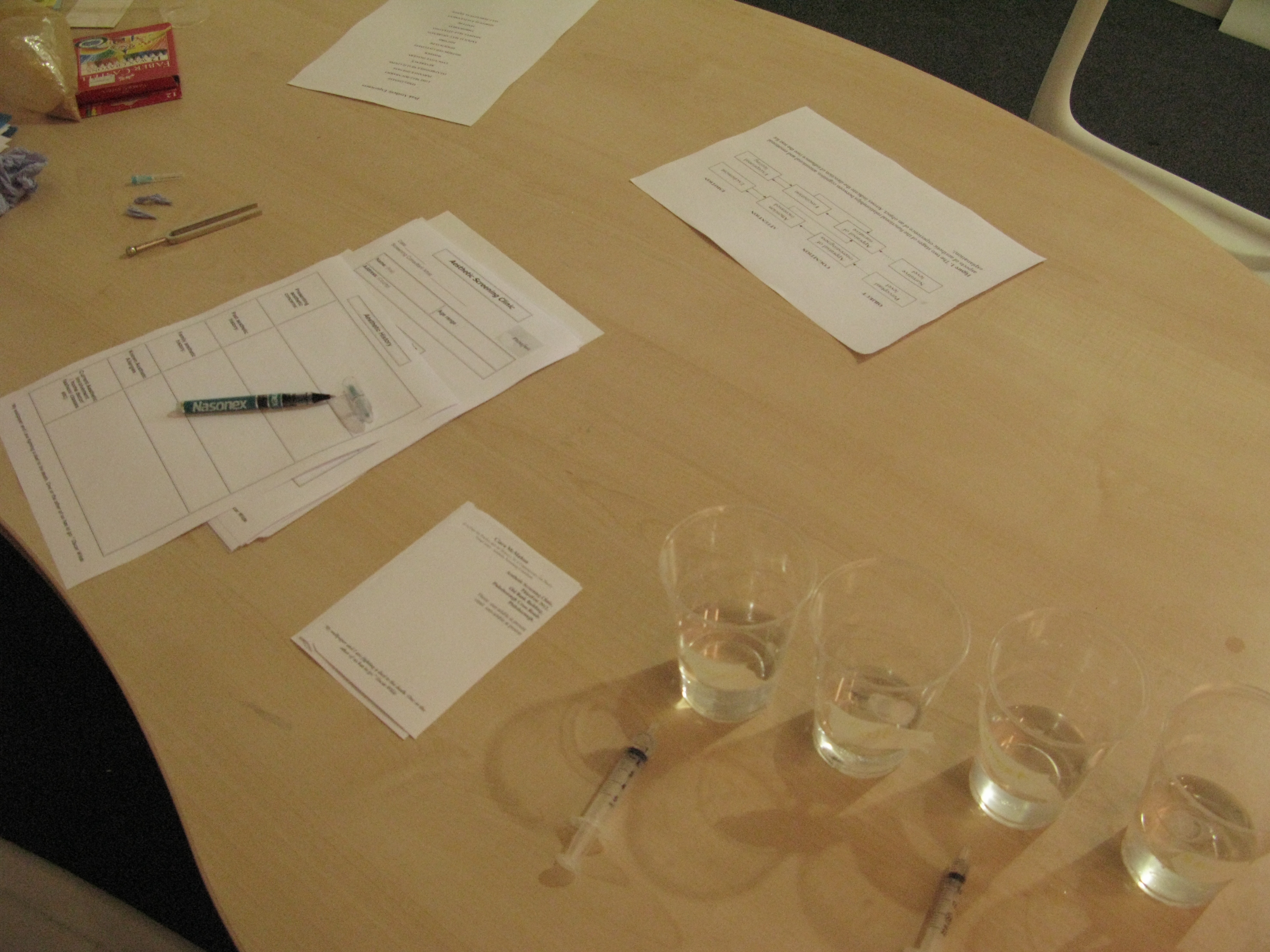

Aesthetic Screening, performative based installation, PhizzFest, 2012

When did your interest in the visual arts first develop and when did you decide to also pursue a career as a visual artist?

I was an associate partner in a large group practice and just felt I wanted to broaden my horizons, to stretch a bit in a totally different way. So I did a portfolio course one night a week with no intention of going into college. The idea was to experiment with a broad range of media ’cause I did music in school, not art, I play the piano and we had to choose one or the other. And then my portfolio teacher said, you know, you can actually do this. So, I said, oh feck it, I’ll put in an application. And to my horror I was accepted because that meant I had to actually make a decision if I wanted to follow through on this or not. So that would be the formal side.

Realistically, my husband always says – and we know each other since second year in medicine – he would always say, if I’m upset, if I feel very strongly about something, if I can’t articulate something, I turn to expressing it visually. So I’ve always drawn, I’ve always painted, I’ve always made things.

You went to NCAD to pursue your degree. Were you practicing as a GP at the same time?

Yes. I employed other GPs to cover me during the day but continued to do late evening surgeries and Saturdays. That was during term time and then during holidays I returned to working more hours in the practice. When I got to final year, I decided to take a step back from the group practice but I continued to work as a GP locum during college holidays, weekends and so on. I did that for a couple of years, through the final year of my degree, through my masters and for a year afterwards. And then I set up this practice here.

Installation shot, Aesthetic Screening, performative based installation, PhizzFest, 2012

What is the inspiration behind the work you produce?

My art practice is heavily influenced by my medicine and my medicine is heavily influenced, I would argue, by my art practice as well. So it works both ways. The artwork is obviously an expression of my interests. I am interested in people and how we negotiate the world through our bodies. We’re embodied individuals and we can’t get away from that. So the work, for me, will always return to that.

I would argue my medicine is heavily influenced by my art because it informs the way I look at the world, it opens up a whole alternative way of seeing and that naturally changes how I interact with patients. The two definitely feed into each other.

One of the art projects that I would be familiar with is Liminality, which stemmed from the Leaky Self collaborative project. What was the impetus behind this project?

I went to a conference. I was there as a GP I think. It was with a philosopher who was doing research with people who had a heart and lung transplant. She was suggesting that people who’ve had a heart transplant can go through an existential crisis sometime between 12 and 20 months after the transplant. They negotiate a shift in their sense of self in response to having a heart or lung from another genetically separate body in their own body. And I thought that was fascinating.

I contacted some of the people who’ve had transplants [through the transplant support] organisation. I happened to meet a recipient who was really keen on working with me outside of the hospital environment and outside of the existing patient transplant organisation for a variety of reasons. We just happened to get on and she wanted to talk about what it was like living with a transplant. A lot of the films or interviews done at the time focused on the whole goriness of the actual transplantation and the immediate aftermath. For me, I was interested in how it was after that and how people continue to live their lives. So the work essentially arose from a meeting of interests between the recipient, the lady I was talking to, and the people she then knew and my own interest in terms of philosophical existential crisis and sense of self.

Time donation 2, installation shot of Liminality, participatory installation, NCAD gallery, 2010. Photo by Susan Walsh.

Liminality had a number of outcomes including a performative installation, a film work and a series of discursive seminars. When you are developing your work, does it depend on the circumstances of the project in terms of what medium you decide to use?

Yeah. I am multidisciplinary. I do draw, I do paint, I make 3-D work, I like video, I like performance. Really shouldn’t the impetus for making the work decide what medium is used? I think sometimes people find it difficult to classify my practice because I work in a range of mediums, but I think the areas that I’m interested in don’t really change, but the outcomes, the actual work can look quite different.

They say in general practice, most GPs, we develop a style of patient interaction and we fool ourselves into thinking that we change our style depending on the patient. I’d hope that within my art practice, my interests remain stable but the medium, the way I mobilize those media, can vary depending on the project.

It’s interesting to hear you talk of patient interaction. Another artwork, Offering Singularity was influenced by your work as a GP and specifically the medical consultation.

At the time of that film, I was juggling setting up a new practice, a general practice, and also a nascent art practice and trying to figure how I could make the two work coherently. And what I realised was, well, what I have to work with is what I’m exposed to every day and that was the issues provoked or evoked by my general practice.

The impetus for the film short was an exhibition influenced by object-orientated ontology which I think is a really interesting paradigm of how to understand what our experience is in the world. I was thinking about a patient who attended the practice. I was sitting in here, I knew they were coming in, I knew that I would be discussing a very difficult consultation with them and that there was a gap between the knowledge that I had and the knowledge that they had sitting outside in the waiting room, a distance of 10 feet. And yet at the same time, we’re breathing the same air, we’re in the same space, we’re embodied in the same way.

That short piece was a combination of needing to make work, working with what I had access to and at the same time thinking quite a bit about object-orientated ontology and how that can play out both within an artwork and within a medicalised environment.

Documentary photograph, Forever Young Singers arriving at SIN nightclub, Dublin as part of Mutual:Esteem, collaborative participatory project, 2010

You’ve touched on how your training and practice as a visual artist has influenced your work as a GP. Could you elaborate on this further?

I think that some visual art resists language. And I think a lot of ill health experiences resist language. Pain is very hard to verbalise. Fundamentally it’s an individual experience. I think having being trained visually, with an the awareness of how difficult it is sometimes to speak, to articulate experiences, can allow or encourage an empathy or an understanding or a space for those kind of experiences to enter into a consultation.

Do you think your practice as a GP has been a help or a hindrance in pursuing a career as a professional artist?

In terms of doing Liminality or other collaborative art work, having the lever of being a medic makes a big difference; it really does, not least because it gives me confidence when exploring research points relating to the body.

So with Liminality, I had no qualms whatsoever about dealing with patients who’d had a transplant. Because I had the psychotherapy training, I also interviewed very intensely participants who were getting involved. I was concerned about the fallout from the project for them. Liminality was asking about their identity and their way of being so I needed people who were solid, at peace with themselves. Obviously they were all free consenting adults, perfectly capable of deciding for themselves whether they wanted to be involved of not. But I really needed to be sure both for them and for myself, as far as I could possibly be, that being involved in the project wouldn’t open a can of worms for them. I guess I wanted to be sure that Liminality wouldn’t ask them something they hadn’t already dealt with themselves already, if that makes sense. And I don’t think I would have had that level of confidence in making that decision if I didn’t have both medicine and psychotherapy training. So in terms of making that kind of work, it’s really useful.

In terms of how am I perceived within the arts scene, I think it might be slightly different and I don’t know whether that’s because of me expecting the medical identity to get in the way, or whether it does actually get in the way. But routinely when I meet people, they go, you’re the doctor, you do a bit of art on the side. But inside, for me, the relationship between the two practices is more nuanced then that.

Time donation, installation shot of Liminality, participatory installation, NCAD gallery, 2010. Photo by Susan Walsh.

What about within the medical world, what is the response to your dual practice?

It’s quite funny. They don’t see me as a visual artist – I do a bit of art on the side. So it’s a hobby. I’ve had people go, well, I cycle. It’s not quite the same. I mean it can be, I don’t know how intensely the cycling was happening but I wouldn’t have thought it was quite the same. And that’s okay. I think most of us find ambiguity difficult.

The Amaranta Family Practice is co-located with a cultural space you founded in 2012 called deAppendix. What was your original vision for deAppendix and do you feel this has been achieved or has it evolved over time?

The original idea was that I couldn’t understand why there wouldn’t be more art within a general practice setting. Because I own the practice, I have freedom to do what I want to do within the premises which meant I could have artists come and be here within the practice and exhibit work. So it was possible to do it. And also, I just wanted to push boundaries and play with patients’ expectations of coming into a healthcare setting. And then also it’s an expression of my experience of working in medicine over the years. I find places that don’t have artwork or have an investment in an aesthetic awareness depressing. And ill health is depressing enough as it is. I don’t need to be working in an environment that adds anything to to that.

I’ve found it difficult to an extent to get artists to exhibit here because their expectations are that I would be only interested in exhibiting work that is medically inspired. For me, I prefer to show challenging, provocative work probably not engaging with medicine directly. The artists can be quite guarded. It’s hard enough to encourage artists to let go of some of their preconceptions of what type of work should be shown. It’s quite nice to get work that pushes a bit.

I curate the shows, so I try to make sure the work that is installed in the front room is a bit more adventurous, that the artists have room to play. The work in the waiting room I curate it quite tightly, subtly hopefully! It’s a waiting room, so patients can be waiting for anything up to half an hour, they can’t go anywhere else, so the material and the content, well I need to be careful about it.

Initially, when I started, I couldn’t afford to pay the artists because I hadn’t a salary myself, as in a medical salary. Now I do so I pay artists a fee, what the VAI recommend. I’d like to do a lot more both in terms of commissioning work, in curating shows and promoting the work but I don’t have time to be going through the hoops that you have to go through in order to get more funding.

Amaranta Family Practice and deAppendix studio, 2013

You said that your patients have been receptive to the artwork. I’m curious to hear more about their response to a cultural space existing within the practice.

Often we have conversations about the work. Like most GPs, I’ll have a bit of banter both at the beginning and the end of the consultation just about how things are and that’s often when we would talk about the show. Often patients will have a chat with my receptionist about the work as well. They tend not to come to the openings. The people who come tend to be the artists and their connections. But whenever we have a show, we do catalogues, and the patients take those, which is kind of interesting, they go very quickly.

How do you create that balance between your work as a GP, a practising artist and as the director and curator of deAppendix?

Most people seem to see them as separate, I don’t, that’s my work, that’s what I do. deAppendix comes and goes in intensity. I’ve had to decrease the frequency of the shows for various kinds of reasons but essentially we do four or maybe five shows a year. Once the show is up and running it kind of chugs along really. I’m in the studio at home every morning for a couple of hours before starting in the GP practice in the morning. Essentially I go to bed very very early and tend not to watch a lot of tv!

Untitled, Limited edition digital print, 20cm ny 200cm, 2010

Are you working on something specific at the moment?

I’m painting at the moment. I’m looking at object-orientated ontology again, but probably pretty counter-intuitively obviously, because I’m so enmeshed in bodies and phenomenology. OOO talks about the egalitarian nature of objects. And for me, as I see it, like a type of medical gaze where you see the liver in bed three or the leg in bed four. As an artist, I think a lot of artists can look at objects with that type of slightly detached gaze as well. The two sit well together in a way.

So, I’m doing a series of paintings around that. I started off doing portraits of my family’s ears. I’ve done a family tree of individual little postcard-sized ears. I was looking at how the genetic variations play out over three generations. Ears are individual, like thumb prints, but there’s still enough of a genetic resemblance visible. So in the ear portraits you’ve got that nice play between intimacy and ambiguity, they’re not immediately identifiable to anyone other that the person themselves, or at least their partner.

I’m also doing a series of portraits of objects that have been in my life for a very long time. There’s an AGA at home that has been a really big part of our family so I’m doing a portrait of that. I guess the body of work is looking at portraiture, playing with it a bit and trying to push that at the boundary of object and not.

The CrossOver Event, participatory collaborative project, Mountjoy Prison, 2008. Photo by Niamh Ferris.

What do you feel the health sciences can learn from the visual arts and, vice versa, what can the visual arts learn from medicine?

I used to have a professor in college, a professor of medicine, and his thing was that medicine is an art and I would agree with that. There’s an awful lot of decision-making that goes on at an unconscious level within medicine, there’s a lot of nuanced information – body language, biochemical information, a whole range of information– we filter through when making decisions. We may not necessarily articulate this process to patients. In my experience that type of filtering is very similar to the decision-making that goes on when you’re making art work. And I think it’s a loss to both fields that there isn’t an acknowledgement of the overlap and an allowance for that liminality, for that bit between the two.