Covid Chronicles

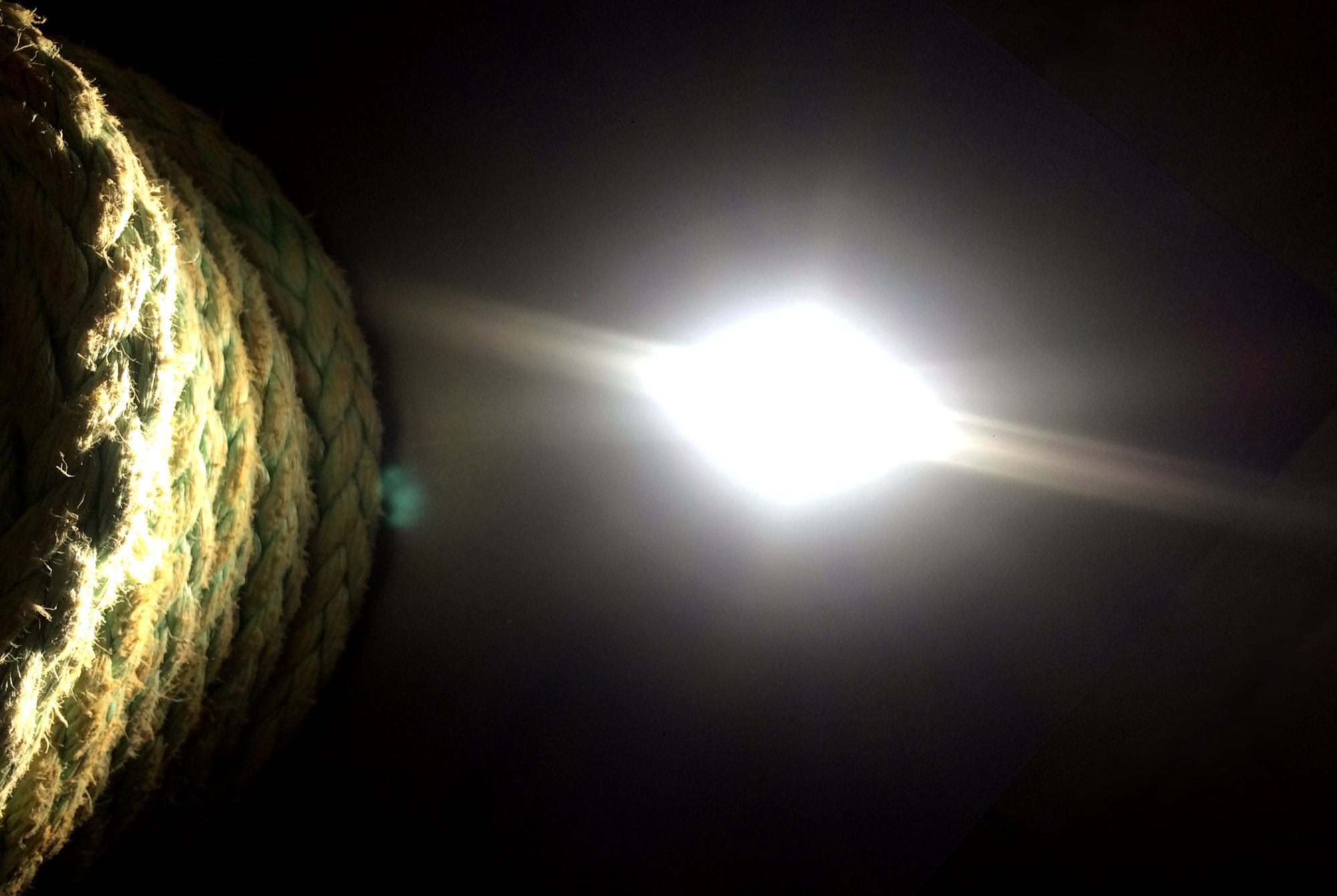

Image from Three Dream Echo by Philip Fogarty

Philip Fogarty is a musician and sound artist. Recent works include two projects staged for the Covid-19 lockdown – The Skies are Empty, a collaboration with cellist Yseult Cooper Stockdale, and Three Dream Echo, a live audience participation event harnessing pandemic restrictions.

His latest project, I Claim Sanctuary, a sound installation in conjunction with Paper Boat, an opera presented by Music for Galway in association with Irish National Opera, will be staged in 2021.

____________________________________________

Thoughts of a musician in the wilderness

The pandemic sails in and with distressing ease rearranges the order of our lives. We settle in for a stand-off, we do what we can to paradoxically channel our lone-wolf tendencies to best effect while simultaneously fostering our community spirit, and we wait.

Macabre, dystopian, omnipresent, the pandemic has been a great leveller; for the arts, an unmitigated disaster. Is there anything at all good I can say about it from an artistic point of view? How about this: modern culture has gone a long way towards establishing the notion that there is some sort of basic difference between performers and audience, artists and so-called punters. The pandemic has, in its turn, gone a long way towards resetting that perception. Anathema for the commercialised arts industry, perhaps, but in terms of societal health and general happiness, this just might be a good thing.

Before we even arrive at the question of artistic merit, I feel that the therapeutic importance alone of art activity for the individual cannot be overstated: I subscribe to the thought that it is we who construct ourselves, and our art is merely an articulation of that.

In nineteenth century rural Ireland, leaving aside what society had to contend with at the time, the perceived difference between performer and audience was far less. At wakes, weddings and fairs, the artistic baton was a communal one.

A modern environment has, conversely, lured us away from the social risks of being our own artists, and the idea of ‘ordinary’ individuals being performers and creators in their own right. We are guided instead towards an art engagement geared exclusively to the consumption of art, and towards an outsourcing of our own creative impulses to carefully marketed professionals, who are deemed as such thanks in large part to the work of promotional campaigns from within the industry itself. The household name, through its very ubiquity in the media, becomes a feature of our daily emotional lives, and a vehicle of sorts for at least part of our own process; the outsourcing is complete.

This is not to argue against getting lost in someone else’s music, I hasten to add; I like a good musical dive into someone else’s ocean as much as the next person. You can’t beat the sense of catharsis that can result from deeply engaging with the work of another with whom you can truly identify.

Image from Three Dream Echo by Philip Fogarty

I will go further and assert that we use the art of others to help in actively constructing our selves, and the image of our selves, both in our own eyes and in those of others. Why ever else, beyond keeping warm and not breaking the law, should it matter what clothes we wear? It matters. Many of us speak through our very dress code. Clothing can be an act of self-expression, and ultimately, of art. In the same way, we may wear music too: because it helps us to become who we are. Irish trad is a whole culture unto itself, as is R&B, or baroque, or early music.

The alchemy of the era of the mass market lies in the directing of our creative focus entirely into that of consumer, punter, and fan. The narrative which describes the member of daily society as artist does not exist, except as corralled into the mortification-fest that is the prime-time TV talent show; a continued reinforcement, if ever there was one, of the message that any attempt at the arts – particularly at modern day folk art – is best left to the professionals. Many of us are, as a consequence, in danger of forgetting ourselves. In historical times, people made their own entertainment, made their own art, composed their own songs. Should living in the twenty-first century preclude such impulses in daily life?

I stated earlier that I subscribe to the thought that it is we who construct ourselves, and that our art is merely an articulation of that.

It can be argued that we do not inherit our identities, and that they are not handed to us. In this view, rather, as observed by Penelope Eckert and Judith Butler among others in their respective contexts, we choose our identities: we embrace or discard our initial circumstances, working with – or fighting against – as the case may be, the first building blocks we find ourselves with: our genetics, our time and place of birth, our families. Down to our very speech utterances, the subsequent construction of our identity is a lifelong process, continually in flux, always a work in progress. Art as personal act, then, can be seen as being often nothing less than an expression of this deeper work in progress, a thought which may go some way towards explaining why we are sometimes so daunted by our own artistic process, and would at times sooner shy away from it. By the same token, though, it argues for how the benefits for our mental and spiritual well-being are deeply rooted.

Maintaining ourselves as active creatives, and not just as passive consumers, facilitates the realisation of our true potential as people, as conscious entities, as processors of experience. It activates that space within our natures from which comes so much of new insight and innovation, enabling us to radically re-engage with our environment and formulate new approaches to the riddle of our existence.

Image from I Claim Sanctuary by Philip Fogarty

In a stretch of my own live paradigms to accommodate the pandemic, I staged the live project Three Dream Echo, in which only a maximum of three visitors could enter, becoming the central element of the piece for three minutes. This project serves as a further vehicle for exploration of each individual as a creative in their own right, addressing the hybrid space of the person as simultaneous listener and performer and leading on from the earlier crowd performance piece The Birds. The pending sound installation I Claim Sanctuary in its turn utilises the input of many who express but do not necessarily declare themselves as artists in an exploration of its themes.

The advent of ubiquitious art-as-exclusively-merchandise product placement, together with that of always-on connectivity and the possibility of instant online shaming has taught us to be wary of our own voices, and to entrust ourselves entirely to the output of others. But to yield completely to such forces, strong though they be, is to block the course of a natural stream within us.

We are nothing if not a species of innovators and adapters; time and again humans have faced down crises ranging from ice ages to world wars and emerged with new knowledge, new thinking, and new methodologies. It may be a good moment to reflect on the essential nature of those creative impulses, and as the pandemic crisis has amplified and in some instances crystalised that dialectic, on how they are part and parcel of the realisation of our happiness and wellbeing, how active artistic practice is an activation of those essential impulses, and how a reset in our relationship to the art process is now, more than ever, worth considering.